The Bagrationi Dynasty

Throughout history, the world has seen many Royal dynasties. These dynasties are created by the kings or queens of respective families who rule throughout multiple generations. Such dynasties include the Valois and the Bourbons of France, the Habsburgs of Austria-Hungary, and the Romanovs of Russia. The Bagrationi Royal dynasty ruled over Georgia between the ninth century A.D. and 1801.

![]() Who is the House of Bagrationi? Most scholars contend that, originally, the Bagrationis were the natives of Speri, which is an old Georgian province. Bagrationi chronicler Sumbat Davitisdze, in his work Life and Activity of the Bagrationis, the Georgian Kings, Their Origin, Time of Their Crowning for Kings of Kartli states that the Bagrationis are descended from the Biblical King David. Prince Davitisdze states, “And four brothers (the sons of Solomon – R.M.) came to Kartli; but one of them named Guaram was chosen to be the eristavi (i.e. the ruler) and he was the eristavi of Kartli and the Bagrationis’ father. And so the Bagrationis of Kartli were the grandsons and relatives of Guaram”.

Who is the House of Bagrationi? Most scholars contend that, originally, the Bagrationis were the natives of Speri, which is an old Georgian province. Bagrationi chronicler Sumbat Davitisdze, in his work Life and Activity of the Bagrationis, the Georgian Kings, Their Origin, Time of Their Crowning for Kings of Kartli states that the Bagrationis are descended from the Biblical King David. Prince Davitisdze states, “And four brothers (the sons of Solomon – R.M.) came to Kartli; but one of them named Guaram was chosen to be the eristavi (i.e. the ruler) and he was the eristavi of Kartli and the Bagrationis’ father. And so the Bagrationis of Kartli were the grandsons and relatives of Guaram”.

There are other chroniclers who also support the Jewish origin of the Bagrationis. The historian of the Georgian King David “the Builder” considers David IV “the Builder” to be the 78th descendant of the biblical King David.

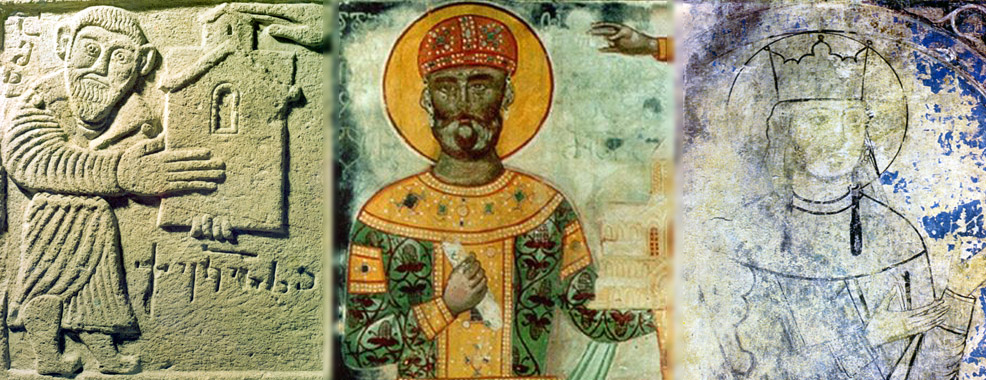

![]() In Georgia, the Bagrationis became famous by the end of the eighth century. From the Bagrationi family came Ashot, eristavi (i.e. regional governor) of Kartli, who is known in history as Ashot the Great. He also had the title of Kurapalat, which is a high Byzantine court title. Ashot the Great established the Bagrationi dynasty of Tao-Klarjeti. The Bagrationis of Tao-Klarjeti (Georgian kingdom) became divided into two main branches: the Tao and the Klarjeti Bagrationis. Ashot’s descendant, Adarnase, was honoured as the first king of the Kartvelians in 888 (although other historical records suggest this took place in either 897 or 899). Ardarnase was the son of David I Kurapalat, and he is known in history as Adarnase II. Adarnase II ruled until 923, and he built upon the foundation of the Klarjeti branch of Bagrationis that was established by his ancestor, who was also named Adarnase (and known to history as Adarnase I).

In Georgia, the Bagrationis became famous by the end of the eighth century. From the Bagrationi family came Ashot, eristavi (i.e. regional governor) of Kartli, who is known in history as Ashot the Great. He also had the title of Kurapalat, which is a high Byzantine court title. Ashot the Great established the Bagrationi dynasty of Tao-Klarjeti. The Bagrationis of Tao-Klarjeti (Georgian kingdom) became divided into two main branches: the Tao and the Klarjeti Bagrationis. Ashot’s descendant, Adarnase, was honoured as the first king of the Kartvelians in 888 (although other historical records suggest this took place in either 897 or 899). Ardarnase was the son of David I Kurapalat, and he is known in history as Adarnase II. Adarnase II ruled until 923, and he built upon the foundation of the Klarjeti branch of Bagrationis that was established by his ancestor, who was also named Adarnase (and known to history as Adarnase I).

![]() Starting with Adarnase II, the title of the Kartvelians’ king was inherited only by the representatives of the Tao branch of Bagrationis (as the successors of Adarnase II). The first king of the united Georgian Kingdom, Bagrat III, belonged to this branch. In contrast, the Klarjeti branch of the Bagrationis came to an end in the early 10th century.

Starting with Adarnase II, the title of the Kartvelians’ king was inherited only by the representatives of the Tao branch of Bagrationis (as the successors of Adarnase II). The first king of the united Georgian Kingdom, Bagrat III, belonged to this branch. In contrast, the Klarjeti branch of the Bagrationis came to an end in the early 10th century.

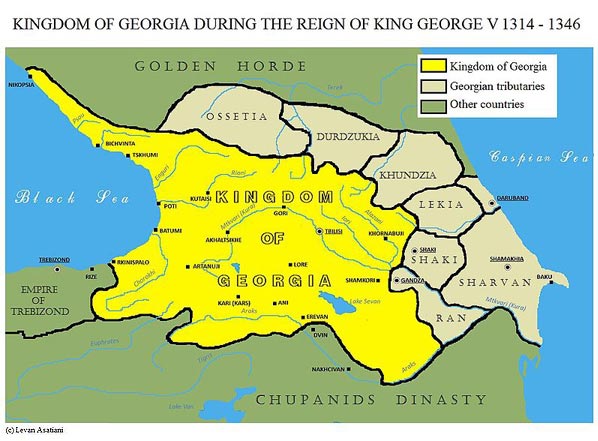

During the reign of David IV “the Builder” (1089 – 1125) and Queen Tamar (1179 – 1213), the Georgian state reached the peak of its power and glory. From the second half of the 15th century forward, the united Georgian kingdom was divided into separate smaller kingdoms. Yet the kingdoms of Kakheti, Kartli, and Imereti remained the domains of the Bagrationis.

The last king of the united Georgia, Giorgi VIII (1446-1466), became the ruler of solely Kakheti in 1466. Consequently, he was the first of the Kakheti branch of the Bagrationis. The Kakheti branch of the Bagrationis continued to rule for centuries, and a descendant, Teimuraz II, became the King of Kartli in 1744. His son, Erekle II, ruled Kakheti. From 1762 onward, Erekle II was the king of the united Kingdom of Kartli-Kakheti. The last descendant of this line to rule was King Giorgi XII. After his demise on 28 December of 1800, the Russian Emperor abolished the Georgian kingdom of Kartli-Kakheti.

The last king of the united Georgia, Giorgi VIII (1446-1466), became the ruler of solely Kakheti in 1466. Consequently, he was the first of the Kakheti branch of the Bagrationis. The Kakheti branch of the Bagrationis continued to rule for centuries, and a descendant, Teimuraz II, became the King of Kartli in 1744. His son, Erekle II, ruled Kakheti. From 1762 onward, Erekle II was the king of the united Kingdom of Kartli-Kakheti. The last descendant of this line to rule was King Giorgi XII. After his demise on 28 December of 1800, the Russian Emperor abolished the Georgian kingdom of Kartli-Kakheti.

THE BAGRATIONIS – DEFENDER OF GEORGIA’S STATEHOOD

The Bagrationis know that their origin stems from the historical and geographical province of Speri (which is present-day Inspiri in Turkey). This southwestern province of the Kartli kingdom has been the subject of various border disputes between Georgia and Armenia for many centuries. The ethnic composition of the population and language of the region was Georgian.

One branch of the Bagrationis settled in Armenia, another in Hereti, and a third branch in Georgia. In time, these respective families became very powerful. The Armenian Bagratuns, notwithstanding their origins, activities, and national self-consciousness, became Armenians. This line of Bagrationis has been in the Transcaucasian area since the second century B.C.

The Armenian Bagratuns, who are descendants of the noble Jew Shambath (149 – 127 B.C.), became crown-holders. By the end of the fifth century, Sahak Bagratuni became the marzpan (governor-general) of the Armenians. In 862, Ashot Bagratun received the title of “sovereign of sovereigns” (ishkhanaz-ishkhani). Subsequently, in 885, he was crowned King of the Armenians. This position persisted until 1045, when King Gagik II (1041 – 1045) was exiled to the Byzantine (Eastern Roman) Empire. Yet one of the branches of the Bagratuns, the so-called Kvirikians, kings of Lore-Tashir (Tashir-Dzorageti), continued to reign. This kingdom continued until the beginning of the 12th century. At that time, the Armenian Bagratuni dynasty came to an end.

The separate line of Bagrationis in Hereti became princes in the eighth century and was raised to kingship by the end of the ninth century. Yet, their dynasty ceased to exist in the early 11th century.

In contrast, the Georgian Bagrationis came to power in the mid-sixth century, when the Kartli Eristavis (roughly equivalent to Dukes) chose their leader. Given the power of neighboring Persia and Constantinople, the early Georgian leaders were reticent to call themselves kings. However, according to Georgian historical tradition, Georgian society at the time referred to these Bagrationis as kings.

In contrast, the Georgian Bagrationis came to power in the mid-sixth century, when the Kartli Eristavis (roughly equivalent to Dukes) chose their leader. Given the power of neighboring Persia and Constantinople, the early Georgian leaders were reticent to call themselves kings. However, according to Georgian historical tradition, Georgian society at the time referred to these Bagrationis as kings.

The ninth century Georgian historical sources (such as Georgian monk Giorgi Merchule) refer to the Jewish origin of the Georgian Bagrationis. These are directly connected to the theory of a biblical origin of the Bagrationis from King David, King of Israel and Judah. The 10th century Byzantine historian Constantine Porphyrogenet refers to this theory. The 11th century Georgian historian Sumbat, the son of David, presented a genealogy of the biblical origins of the Georgian Bagrationis. By the end of the 10th century, the Royal throne of the united Kingdom of Georgia was occupied by a member of the House of the Bagrationi (Bagrat III, 975 – 1014). The understanding regarding the Bagrationis biblical origin and their divine power in Georgia (from God’s promise to King David that a descendant of his would always reign) is also shared by the Georgian church.

The ninth century Georgian historical sources (such as Georgian monk Giorgi Merchule) refer to the Jewish origin of the Georgian Bagrationis. These are directly connected to the theory of a biblical origin of the Bagrationis from King David, King of Israel and Judah. The 10th century Byzantine historian Constantine Porphyrogenet refers to this theory. The 11th century Georgian historian Sumbat, the son of David, presented a genealogy of the biblical origins of the Georgian Bagrationis. By the end of the 10th century, the Royal throne of the united Kingdom of Georgia was occupied by a member of the House of the Bagrationi (Bagrat III, 975 – 1014). The understanding regarding the Bagrationis biblical origin and their divine power in Georgia (from God’s promise to King David that a descendant of his would always reign) is also shared by the Georgian church.

Georgia has consistently had a Bagrationi Royal dynasty. By the end of the 15th century, when united Georgia again was dissolved into separate kingdoms (this time, Kartli, Kakheti, and Imereti), the Royal throne was occupied in each kingdom by the representatives of different branches of the Bagrationi Royal house. The Bagrationis have been kings since the sixth century and “Kings of Kartvels” (Georgians) since the 9th century. Provided that one accepts the theory that they are also descendants of the Parnavazians branch, the Bagrationi history may be said to have started from the 4th century B.C.

Throughout history, the Georgian king has served as a symbol of unity of statehood. After annexation, the Russian empire was very cognizant of this, which is why the members of the Georgian Royal family were exiled from their country.

THE FIRST APPEARANCE OF THE BAGRATIONIS

IN KARTLI (OR MODERN DAY GEORGIA)

The Caucasiological historiography differs slightly from the aforementioned Bagrationi history in that it considers the Georgian and Armenian Bagratids as stemming from the same dynasty. The heads of the Georgian branch were separated from the Armenian princes and settled in Georgia at the end of the eighth century. Some experts in Caucasian studies suggest that the Bagratid family is of Chanish origin. Over time, one of the branches became Armenized.

Between 1990 and 2000, the Institute of Manuscripts conducted four scientific and restoration expeditions to study 141 Georgian manuscripts that were discovered in 1975 in St. Catherine’s monastery in Sinai. This expedition led to the important discovery of a unique volume (N/Sin 50). The volume, which is clearly missing an introduction and conclusion, consists of three sections: the “Moktsevai Kartlisai” with “Life of St. Nino”, the “Activities of Ioane Zedazneli and His Disciples”, and the “Martyrdom of Abibo of Nekresi”. The work was compiled or copied in the early 10th century.

The works of the “Activities of Ioane Zedazneli and His Disciples” are unique and not witnessed by any other sources. They contain inserted comments that differ from the rest of the text. These comments contain descriptions of the libraries of Jvari, Zedazeni, and David Gareja; descriptions of the monastery treasures with a reference to the donors (the House of Rustaveli amongst others); and family epitaphs with the exact genealogy and chronology of the Kartli kings. The comments were determined to have been made between the end of the eighth and the beginning of the 10th centuries, but most of them were probably written at the end of the eighth century.

In one of these comments, there is a reference to Adarnase, whose image is on the Jvari relief (usually referred to as the Jvari pedestal inscription). This is the same Adarnase (Atrnerse) who played a leading part in the discord between the Georgian and Armenian churches in the beginning of the eighth century. He was a great supporter of Kiron, the Catholicos of Kartli, during an international conflict concerning orthodoxy. According to the evidence provided by N/Sin-50, a genealogical table of the Kartli princes of the sixth and seventh centuries is as follows: Guaram the Great – Stepanoz – Demetri (his brother) – Latavri (his sister) – Adarnase Mampal – Guaramavri (his wife).

In contrast, the aforementioned archaeological find of Moktsevai Kartlisai does not link the Kartli rulers with the future Tao-Klarjeti Bagrationis. In fact, the author does not address this issue at all. If the work was compiled in the ninth or 10th centuries, it could not have avoided identification of the Bagrationi family as the family was mentioned in virtually all sources of that time and for several centuries thereafter. Thus, it is difficult to ensure whether these families are connected with the possible linkage of Juansher. It just isn’t directly addressed in the text. Only in the titles of the royals, which are not in all the lists (including the so-called Anna and Mariam lists), can we read the following: “the thirty-ninth King of Kartli Kurapalat Guaram Bagratoani”, “the fortieth Prince of Eristavis of Kartli, Stepanoz, son of Guaram Kurapalat, Bagratoani”. There is only one reference in the text that points to links between the Tao-Klarjeti Bagrationis and the descendants of Guaram and Stepanoz. When Caesar Herakles murdered Stepanoz, and Kartli was occupied by Adarnase (the son of Bakur), Juansher refers to the heirs of Stepanoz who remained in Klarjeti. Additionally, he also mentions one Prince, who was a relative of David the Prophet, named Adarnase. This Adarnase was a nephew of Adarnase the Blind. His father was a relative of the Bagrationis, and the Greeks made him a prince in Armenia. Murvan the Deaf visited Guaram Kurapalat’s children in Klarjeti and stayed there. According to Juansher, it was Adarnase who asked Archil Erismtavari to allow him to settle on his territory. He was successful in this request.

Matiane Kartlisai continues Juansher’s narration as follows: Archil’s son, Juansher, marries Latavri, a daughter of the aforementioned Adarnese. Latvari’s mother did not initially support the marriage as she was unaware that the Bagrationis are descendants of David the Prophet. In the end, the matter is settled harmoniously, and the descendants of Adarnese (the son of Bakur) and the Bagrationis become relatives. According to this record, this is how the Bagrationis became related to the Kartli Erismtavaris family.

The Bagrationi origins are described quite differently in the Chronicle by Sumbat, the son of David: seven brothers came from the land of the Philistines and settled first in Armenia. Subsequently, four of the brothers went to Kartli. The Kartli Bagrationis descend from one of them: Guaram Eristavi. The N/Sin-50 indicates that: Guaram, Stepanoz, and Adarnerse (Kartli Erismtavari) were father, son, and grandson. This evidence supports and reinforces Sumbat’s version.

Further evidence of the accuracy of the Sumbat account is the precision of familial relationships. Translated into English, the document reads in part, “Bagrationis are the grandchildren and relatives of Guaram”. Given that other sources indicate that the mother of the Bagrationis was Latavri, the granddaughter of Guaram Kurapalat, the Sumbat version gains more credibility.

Therefore, the Georgian Bagrationis cannot be the direct close relatives of the Armenian Princes Ashot the Blind and Vasak. According to N/Sin-50, the Bagrationis were in Kartli before they became related to the Kartli Erismtavaris in the early seventh century.

Like Matiane Kartlisai, the Bagrationis and the Kartli Erismtavaris are related to each other. The aforementioned Latavri was married to a representative of the Bagrationi family. When translated into English, just as Sumbat refers to Guaram the Great as the “father of the Bagrationis”, N/Sin-50 states that Guaram’s granddaughter Latavri was the “mother of Bagratunians”.

The additional expression “mother of Bagratunians and Kurapalatians” points to the unification of the Kartli Princes (Kurapalatians, the descendants of Guaram Kurapalat) and the Bagrationi family. During the same era, which was the eighth and ninth centuries, being a Kurapalat was a privilege reserved only for the Bagrationis. This suggests that the Bagrationis were not yet kings (until Adarnase II at the end of the ninth century. Otherwise, it is difficult to understand mentioning the Bagrationis as being Kurapalats and not kings. The evidence provided by N/Sin-50 also justifies one more supposition; namely, Mtskheta Jvari became a burial place for the Kartli Princes, at least for those who participated in its building: Guaram, Stepanoz, Demetre, Adarnase and members of their family. Yet the Bagrationis were also buried there. According to the Mtskheta Jvari, there was also buried the “mother of Bagratunians – with her son and son of her daughter”. The children of the mother of the Bagrationis would certainly have been Bagrationis. Given its cultural significance, Mtskheta Jvari would have become a burial place for the Bagrationis only through unification with the Kartli Princes. Therefore, it is very likely that the Bagrationis became Kartli princes, then kings, and were the legal descendants of Pharnavazians and Gorgasalians.

HERALDRY OF THE BAGRATIONI ROYAL DYNASTY

The use of symbolic signs is a well-established historical tradition. Heraldry is the art of armorial achievements, including coats of arms. There are different types of coat of arms: patrimonial, territorial, and sovereign. The latter are often concurrent with the coat of arms of the ruling dynasty. The Georgian nation has a rich history and a long heraldic tradition.

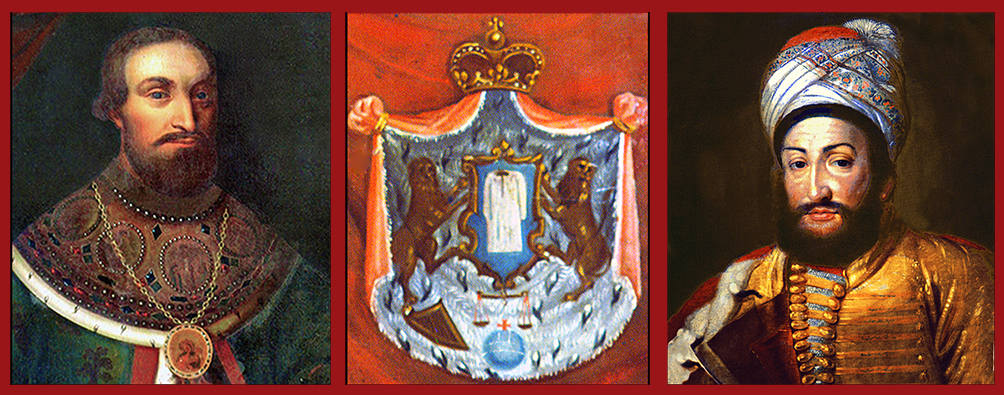

![]() The roots of the ancient Georgian heraldic symbols have come from totemic thought. Georgia is fortunate in that numerous historical seals with emblems have been preserved. A state gold seal of King Giorgi III (1156-1184) is of particular importance among the old Georgian symbols. It is characterized by an emblem of St. George. Seals with coat of arms became particularly widespread in Georgia in the 18th century. By the end of the 18th and the early 19th century, Georgian heraldry had come under the influence of the heraldic traditions of both Western Europe and Russia. The first Georgian patrimonial coat of arms appears only in the beginning of the 18th century, when the King of Kartli was Vakhtang VI (1703 – 1724). In 1724, King Vakhtang visited Russia and became acquainted with the heraldry of that country.

The roots of the ancient Georgian heraldic symbols have come from totemic thought. Georgia is fortunate in that numerous historical seals with emblems have been preserved. A state gold seal of King Giorgi III (1156-1184) is of particular importance among the old Georgian symbols. It is characterized by an emblem of St. George. Seals with coat of arms became particularly widespread in Georgia in the 18th century. By the end of the 18th and the early 19th century, Georgian heraldry had come under the influence of the heraldic traditions of both Western Europe and Russia. The first Georgian patrimonial coat of arms appears only in the beginning of the 18th century, when the King of Kartli was Vakhtang VI (1703 – 1724). In 1724, King Vakhtang visited Russia and became acquainted with the heraldry of that country.

Yet there are earlier examples of heraldry in Georgia, with the Bagrationis prominent amongst the examples. On the gravestone of Queen Tinatin, the wife of Kakheti King Levan I (1518 – 1574), there is distinctive heraldry. On the shield of the coat of arms, there is an inescutcheon (smaller shield within the main shield) with the Lord’s tunic, which is the most important sacred relic of the Georgian Orthodox church. This holy tunic remains preserved in Georgia. Additionally, two lions serve as supporters for the shield. In addition to the Lord’s tunic, the remainder of the shield is quartered. On the upper left quarter, there is a sceptre and sword that symbolize the military and royal power of the Georgian kings. On the upper right quarter, there is the harp of the biblical King David and his catapult. These heraldic symbols reinforce the theory that the Bagrationis descend from the biblical King David. In the lower left quarter, there are scales. These symbolize the justice of King Solomon, son of the biblical King David. Within the lower right hand quarter, there should have been a royal orb to be consistent with the coats of arms of the Kartli and Kakheti kings. It is unclear what is actually on the lower right quarter of Tinatin’s gravestone. Over the shield, there is a crown that resembles other European royal crowns. Surrounding the armorial achievement is a verse from the biblical Psalms: “The Lord hath sworn in truth unto David; He will not turn from it; of the fruit of the body will I set upon the throne” (Psalm 132 : 11).

From the coats of arms that have been preserved, the next chronological evidence is the armorial achievement of Queen Tamar, wife of the Imereti King Alexander III (1639 – 1660). The design is as follows: the shield is divided into four quarters. In the upper left quarter, there is a harp of David the Prophet (the biblical King David), in the upper right quarter David’s catapult, in the lower left quarter a warder, and in the lower right quarter a sceptre and a sword. The shield is surmounted by a crown. The Lord’s tunic does not appear on Queen Tamara’s coat-of-arms; the tunic appears only on the Imereti Bagrationi armorial achievements at the beginning of the 19th century.

A third historical armorial achievement that has been preserved belongs to the Kakheti King Vakhtang VI (1703 – 1724). Originally, this achievement belonged to King Vakhtang’s uncle, the Kartli King Giorgi XI (1676 – 1688, 1703 – 1709). Another coat of arms belongs to the Kartli King Kaikhosro (1709 – 1711), who was King Vakhtang’s elder brother. Vakhtang VI had his own coat of arms from 1726 – 1737. In 1735, Vakhushti Batonishvili, the son of Vakhtang VI, drew up an important map of the Caucasus. Within this map are the coat of arms of the countries and regions that appear on it, including those of the Bagrationi family.

A third historical armorial achievement that has been preserved belongs to the Kakheti King Vakhtang VI (1703 – 1724). Originally, this achievement belonged to King Vakhtang’s uncle, the Kartli King Giorgi XI (1676 – 1688, 1703 – 1709). Another coat of arms belongs to the Kartli King Kaikhosro (1709 – 1711), who was King Vakhtang’s elder brother. Vakhtang VI had his own coat of arms from 1726 – 1737. In 1735, Vakhushti Batonishvili, the son of Vakhtang VI, drew up an important map of the Caucasus. Within this map are the coat of arms of the countries and regions that appear on it, including those of the Bagrationi family.

During the period of the Kartli-Kakheti King Erekle II (1744 – 1798) the Bagrationi armorial achievement shares a State function as well. During this period, heraldry became prominent in the kingdom. This includes a Bagrationi coat of arms that appears on the seal of a ratification deed of the Georgievsk Treaty in 1783. This was the first officially confirmed state armorial achievement of the Kingdom of Georgia. Similarly, between 1765 and 1766, heraldic symbols of the Bagrationis appear on coins minted in Tbilisi, which is the first time this occurs in Georgian history.

The next chronological Bagrationi armorial achievement belongs to Giorgi XII, King of Kartli-Kakheti. His arms were also the state arms of the Kartli-Kakheti Kingdom. During the short period of the last governor of Kartli-Kakheti (1800-1801), Prince David XII also had an armorial achievement.

The next chronological Bagrationi armorial achievement belongs to Giorgi XII, King of Kartli-Kakheti. His arms were also the state arms of the Kartli-Kakheti Kingdom. During the short period of the last governor of Kartli-Kakheti (1800-1801), Prince David XII also had an armorial achievement.

From 1801, east Georgia (the Kartli-Kakheti Kingdom) fell under the domination of the Russian Empire. This affected the heraldry of that time, and various changes occurred in stylistic expressions. Thus, the first period of independent Georgian heraldry came to the end, ushering in a second era that is typically referred to as the Russian-European period. During this era, Bagrationi heraldry was reduced with historical evidence only of the armorial achievement of Prince David (XII). Famed heraldist M. Vadbolski refers to heraldry within this era as the “protectorate period”.

There are even fewer surviving records of the heraldic traditions of the Bagrationi dynasty in the Imereti Kingdom. Only a few coats of arms have been preserved:

There are even fewer surviving records of the heraldic traditions of the Bagrationi dynasty in the Imereti Kingdom. Only a few coats of arms have been preserved:

- 1) those of Queen Tamar, the first wife of the Imereti King Alexander III (1630 – 1660);

- 2) those of the Imereti King Alexander V (1720 – 1752); and

- 3) those of the Imereti King Solomon II (1789 – 1810).

In honour of Old Colchis, since the latter half of the 18th century, a sheep is represented on the coat of arms to symbolize this ancient country and its glorious history.

There is also heraldry from non-Royal ancillary Bagrationi families. By the end of the 15th century, the single state of Georgia was partitioned into several political units. These political units were governed by the Royal branches of Kartli, Kakheti, and Imereti. In the early 16th century, a branch of the princely Mukhranbatoni family separated itself from the Kartli Bagrationi Royal House. From 1512 to 1801, this family owned the Mukhrani princedom, which did not have individual sovereignty. This princely branch did not have a unique armorial achievement until the 19th century, when the family inappropriately usurped the arms of the already deposed Royal family of Georgia (Bagrationi-Gruzinski). One of these early Mukhranbatoni coats of arms belong to the descendants of the King Iese of Kartli, who migrated to Russia in 1757. This coat of arms was confirmed by the Emperor Alexander I of Russia on 4th October of 1803. It was listed in the “common register of coats of arms”, part VII (number 2), as a patrimonial coat of arms of the Bagrationis themselves.

Another branch of Bagrationis with heraldry are the Davitishvilis. In the early 15th century, a branch of the Bagrationis, the Davitishvilis, separated from the Kakheti Bagrationi Royal House. The family settled in Kartli due to intertribal tension. By the 18th century, the Bagrationi-Davitishvilis also had their own coat-of-arms.

An additional heraldic Bagrationi line is the Babadishs. In the second half of the 17th century, the line of Bagrationi-Babadishs separated from the Kakheti Bagrationi Royal House. By the 18th century, this line had established its own coat-of-arms that was later confirmed by the Russian Empire. Within this armorial achievement were royal symbols of the Bagrationi family.

An additional heraldic Bagrationi line is the Babadishs. In the second half of the 17th century, the line of Bagrationi-Babadishs separated from the Kakheti Bagrationi Royal House. By the 18th century, this line had established its own coat-of-arms that was later confirmed by the Russian Empire. Within this armorial achievement were royal symbols of the Bagrationi family.

Presently, there are more than 50 armorial variants that belong to the Georgian Kings of the Bagrationi family. The arms of the Princes Gruzinski (the descendants of King Erekle II) were confirmed within the Russian Empire on 22nd January of 1886. This confirmation was included in the common register of arms, specifically Vol. XIV, №2. Other armorial bearings for the Bagrations dynasty are recorded in various historical seals, gravestones, and private articles.

OFFSHOOTS OF THE BAGRATIONI ROYAL HOUSE: 16th – 18th CENTURIES

The main Royal Bagrationi line spawned many lines. Given a lack of consistency in succession rules, some of these offshoot lines were significant in the history of Georgia. For classification purposes, it is easier to break these groupings into stages.

The initial stage of collateral lines was regarded as a “Tekhili” (a turning point in Georgian history). In the 13th century, royal power was devolving and foreign affairs became more complicated. In conjunction with the general weakening of the throne, Georgian princes engaged in violent struggles for dominance within their domains. From 1298 to 1318, several kings ruled simultaneously. This gave rise to the collateral lines of descent that became important for the first time since Georgia coalesced into a country. The era was known for provincial kings with reduced centralized authority.

The subsequent “Orianoba” stage further weakened centralized power and broke up the administrative machinery. This, in turn, affected the House of Bagrationi. The interrelationship between the dissolution of the united Georgian feudal monarchy and the meddling of offshoot Bagrationi family lines is strong. Interfamily rivalry led to power grabs. This resulted in a lack of governmental stability and continuity that ultimately resulted in the country becoming splintered.

After the collapse of the united kingdom of Georgia, the various Batonishvili (princes) and the Bagrationi family struggled to maintain their rights within the independent kingdoms. The rights of inheritance that were established in previous centuries were no longer respected; power vacuums and political intrigue often determined the inheritance instead. This led to a reduction in the status of the Batonishvili amongst the general populace. Unlike in previous centuries, these princes were no longer referred to as prince-kings, and it was clear that these off-shoot branches lacked sovereignty in their own right.

Throughout the 14th and 15th centuries, these offshoot branches, although reduced in status, remained linked with the royal Bagrationi family. But from the 16th century, as new principalities were established, some of these lines did not solely retain the Royal name of Bagrationi. These lines were called Natomi Mepeni, and historical examples of these collateral lines are Bagration-Gochashvili, Bagration-Mukhranski, Bagration-Davitishvili, Bagration-Babadishi, and Bagration-Ramazishvili.

This brief review demonstrates that collateral offshoot branches have caused administrative challenges for the Royal Bagrationi family for many centuries, including being instrumental in the collapse of the united Georgian kingdom.

ON THE ORIGINS OF THE GREAT ROYAL FAMILY OF BAGRATIONI – GRUZINSKI

The history of the Bagrationi Royal family is organically connected with the Georgian people for centuries. The Bagrationi Royal Dynasty, which headed the Georgian state for more than a thousand years, rightly occupies a place of honour amongst Christian dynasties. Over the millennia, representatives of the Bagrationi Royal dynasty made significant contributions to the country’s military, political evolution, and cultural development. The dissolution of the unified Georgian kingdom led to the establishment of the Kartli, Kakheti, and Imereti Royal branches of the House.

The history of the Bagrationi Royal family is organically connected with the Georgian people for centuries. The Bagrationi Royal Dynasty, which headed the Georgian state for more than a thousand years, rightly occupies a place of honour amongst Christian dynasties. Over the millennia, representatives of the Bagrationi Royal dynasty made significant contributions to the country’s military, political evolution, and cultural development. The dissolution of the unified Georgian kingdom led to the establishment of the Kartli, Kakheti, and Imereti Royal branches of the House.

According to the 1801 manifest of Russian Emperor Alexander I, the Bagrationi Royal rule of the Kartli-Kakheti kingdom was illegally abolished,  and Georgia was declared to be a Russian province. Despite the illegal military overthrow, the Bagrationi Royal family continued to make significant contributions to Georgia and the greater Russian Empire in the military, scientific, artistic, literary, and other spheres. Within the Russian Empire, children of the Kartli-Kakheti (Georgian) kings Erekle II and Giorgi XII had official titles of “Georgian Princes and Princesses”. In Russia, the honorary style for these Royals was “the Most Respectful”. In 1804 and 1812, the Russian government decided that only the sons of Georgian (Kartli, Kakheti) kings were permitted to enjoy this title. These descendants enjoyed the title of “Georgian prince” (Gruzinski).

and Georgia was declared to be a Russian province. Despite the illegal military overthrow, the Bagrationi Royal family continued to make significant contributions to Georgia and the greater Russian Empire in the military, scientific, artistic, literary, and other spheres. Within the Russian Empire, children of the Kartli-Kakheti (Georgian) kings Erekle II and Giorgi XII had official titles of “Georgian Princes and Princesses”. In Russia, the honorary style for these Royals was “the Most Respectful”. In 1804 and 1812, the Russian government decided that only the sons of Georgian (Kartli, Kakheti) kings were permitted to enjoy this title. These descendants enjoyed the title of “Georgian prince” (Gruzinski).

In 1833, the Russian government adopted an additional decision regarding which grandsons of Erekle II and Giorgi XII were granted the title of “Georgian prince” (Gruzinski), and this title eventually became their surname. The representatives of all other branches of the Bagrationi family had only a title of prince, which was below the title of Georgian prince. Examples of other families that only had the title of prince are Bagration-Mukhranski, Bagration-Davitashvili, and Bagration-Babadishi.

In 1833, the Russian government adopted an additional decision regarding which grandsons of Erekle II and Giorgi XII were granted the title of “Georgian prince” (Gruzinski), and this title eventually became their surname. The representatives of all other branches of the Bagrationi family had only a title of prince, which was below the title of Georgian prince. Examples of other families that only had the title of prince are Bagration-Mukhranski, Bagration-Davitashvili, and Bagration-Babadishi.